Valley Forge National Historical Park

Encampment of the Continental Army in the winter of 1777-1778

“The unfortunate soldiers were in want of everything; they had neither coats nor hats, nor shirts, nor shoes. Their feet and their legs froze until they were black, and it was often necessary to amputate them.”

~ Marquis de Lafayette ~

Valley Forge National Historical Park, located about twenty miles from Philadelphia, is one of the national parks that I always wanted to visit, but did not believe I would have the opportunity, believing it too far out of the way – nothing could be farther from the truth. A small detour, if you are planning a visit to Philadelphia, the park is easily accessible and worth the drive. Do start your visit at the Visitors Center – great displays, maps, and additional information

Below is a history, of Valley Forge, and its significance in the American story, courtesy of the National Parks website:

“In 1777 British strategy included a plan to capture Philadelphia, the patriot capital. To accomplish this, the British commander in chief, Sir William Howe, landed nearly 17,000 of His Majesty’s finest troops at the head of Chesapeake Bay. To oppose them, General George Washington marched his 12,000-man army from New Jersey. People often picture the Continental Army of 1777 as a ragtag bunch of inexperienced fighters. But Washington’s men fought with skill and were often on the offensive while campaigning against superior numbers of professional soldiers.

Although they lost two key battles, as well as Philadelphia, to the British, Washington’s soldiers emerged from these experiences with a renewed confidence in their fighting abilities. They only needed a little more training to reach their full potential.

As wintry weather approached, armies often withdrew to fixed camps. Transportation problems made large-scale winter operations infeasible. In choosing a site for quarters, Washington had to balance the Continental Congress’s wish for some type of winter campaign aimed at dislodging the British from the capital against the needs of his weary and poorly supplied army. By mid-December he had decided to encamp at Valley Forge.

From this location, twenty miles northwest of Philadelphia, the army was close enough to maintain pressure on the British yet far enough away to prevent a surprise attack. While the soldiers who entered camp on December 19, 1777, were not well-supplied, they were not downtrodden. This is attested to by an anonymous observer who recounted his visit to Valley Forge in the New Jersey Gazette on December 25:

‘I have just returned from spending a few days with the army. I found them employed in building little huts for their winter quarters. It was natural to expect that they wished for more comfortable accommodations, after the hardships of a most severe campaign; but I could discover nothing like a sigh of discontent at their situation…On the contrary, my ears were agreeably struck every evening, in riding through the camp, with a variety of military and patriotic songs and every countenance I saw, wore the appearance of cheerfulness or satisfaction.’

Army records and eyewitness accounts speak of a skilled and capable force in charge of its own destiny. Rather than wait for deliverance, the army located supplies, built log cabins to stay in, constructed makeshift clothing and gear, and cooked subsistence meals of their own concoction. Provisions, though never abundant in the early months of the encampment, were available.

Shortages of clothing did cause severe hardship for a number of men, but many soldiers had a full uniform, and the well-equipped units patrolled, foraged, and defended the camp. The sound that would have reached your ears on approaching the camp was not that of a forlorn howling wind, but rather that of hammers, axes, saws, and shovels at work.

Under the direction of military engineers, the men built a city of 2,000-odd huts laid out in parallel lines along planned military avenues. The troops also constructed miles of trenches, five earthen forts (redoubts), and a state-of-the-art bridge over the Schuylkill River.

Disease, not cold or starvation was the true scourge of the camp. Army returns reveal that two-thirds of the nearly 2,000 men who perished died during the warmer months of March, April, and May, when supplies were more abundant. The most common killers were influenza, typhus, typhoid, and dysentery. Dedicated surgeons, capable nurses, a smallpox inoculation program, and camp sanitation regulations limited the death tolls.

Perhaps, the most important outcome of the encampment was the army’s maturation into a more professional force. The Continental Army was primed and ready to move on to the next level just as a charismatic former Prussian army officer, Baron Friedrich Wilhelm Augustus von Steuben, arrived in camp in February 1778.

Von Steuben’s hands-on training program helped the army become a more proficient marching machine. The Baron inspired a “relish for the trade of soldiering” that gave the troops a new sense of purpose and helped sustain them through many trials as they stuck to the task of securing independence.

On May 6, 1778, the army joyously celebrated France’s alliance with and formal recognition of the United States as a sovereign power. The expected arrival of the French greatly altered British war plans and triggered their evacuation of Philadelphia in June.

Washington rapidly set troops in motion to bring on a general engagement with the enemy. On June 28, at the Battle of Monmouth, N.J., Washington’s men demonstrated their improved battle prowess when they forced the British from the field.

By summer Washington could claim that the war effort was going well. Valley Forge was not the darkest hour of the Revolutionary War; it is a place where an already accomplished group of professionals stood their ground, honed their craft, and thwarted one of the major British offensives of the war.” http://www.nps.gov/vafo/index.htm

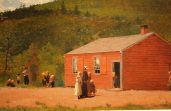

This is what the cabins looked like that men built, to provide themselves with shelter.

Me standing in front of the National Memorial Arch, which was dedicated on June 19, 1917, and refurbished in 1996-1997, by the Free Masons of Pennsylvania.

‘

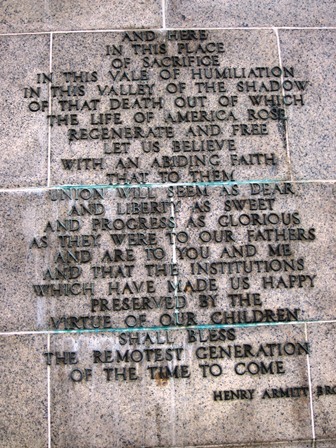

Kate standing inside the National Memorial Arch, reading the inscriptions.

One of the inscriptions

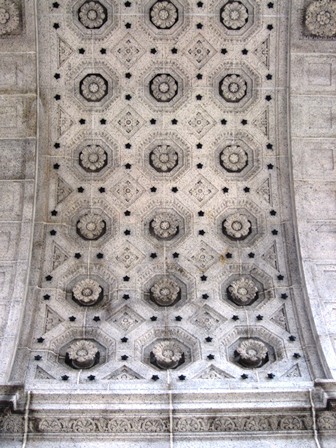

Detail of the interior of the Arch

The headquarters for General Washington and his staff, and where Mrs. Washington also stayed, when visiting her husband. The house and the Valley Forge were owned by ironmaster Isaac Potts, who was paid 100 Pennsylvanian pounds for its use.

Interiors of the Potts house, set up as office space, for the Army.

Sleeping quarters for the General, his staff, and his servants.

The kitchen

Kate in the kitchen

Me standing by the oven.

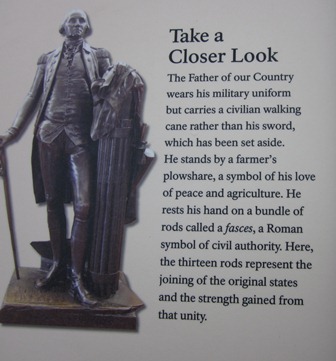

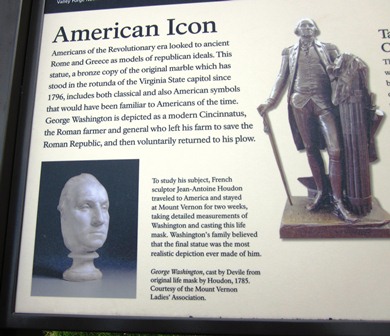

A statue of George Washington, considered by his family to best capture the President and General. The original stands in the rotunda of the capitol of Virginia.